Loner with Hag, Irix and Spinster (Self)

Loner

yarn, snake skin, faux snake skin, cow leather with hide, brass, fire agate, waxed thread, steel grommets, iron oxide stained oak

51" x 4" x 62"

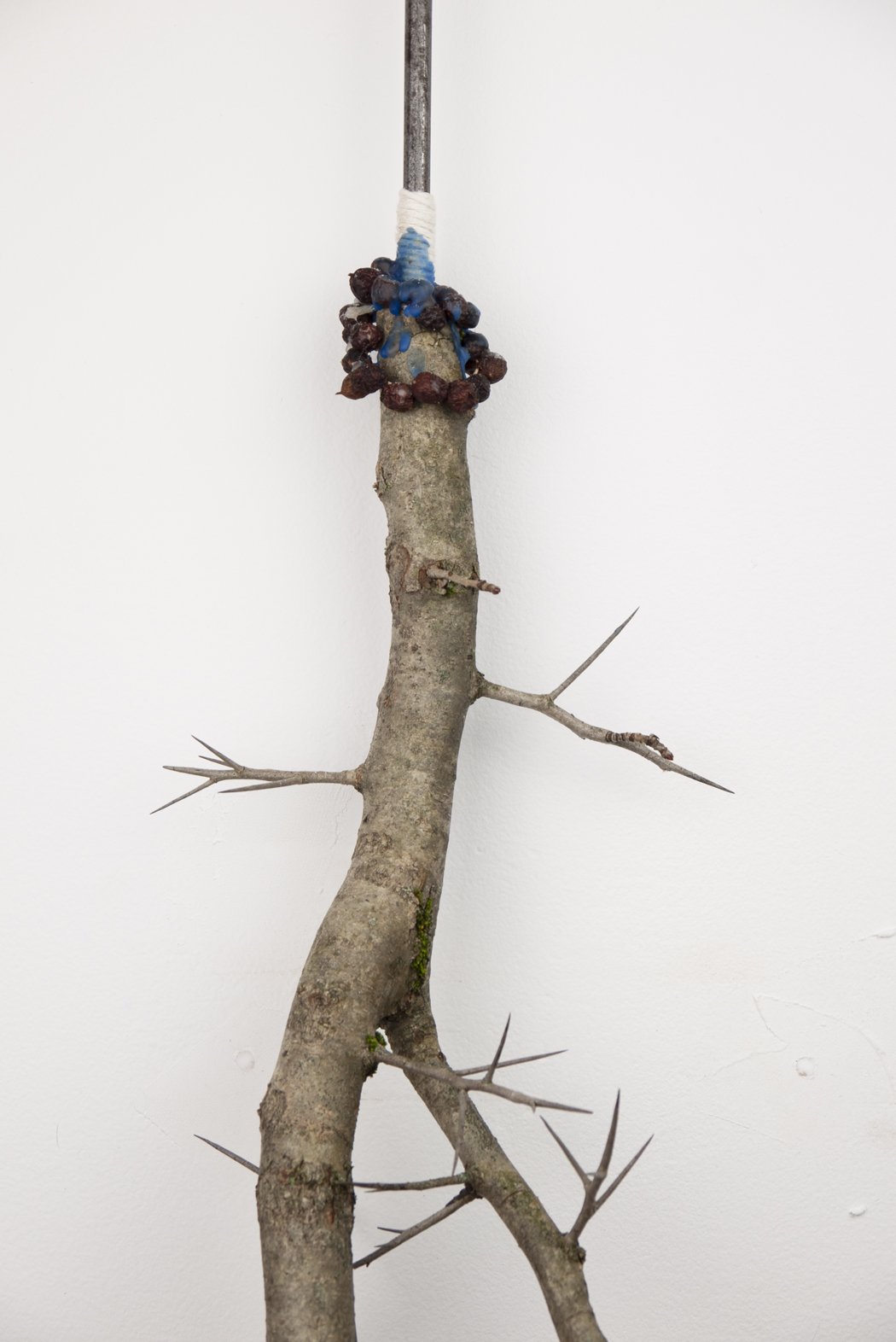

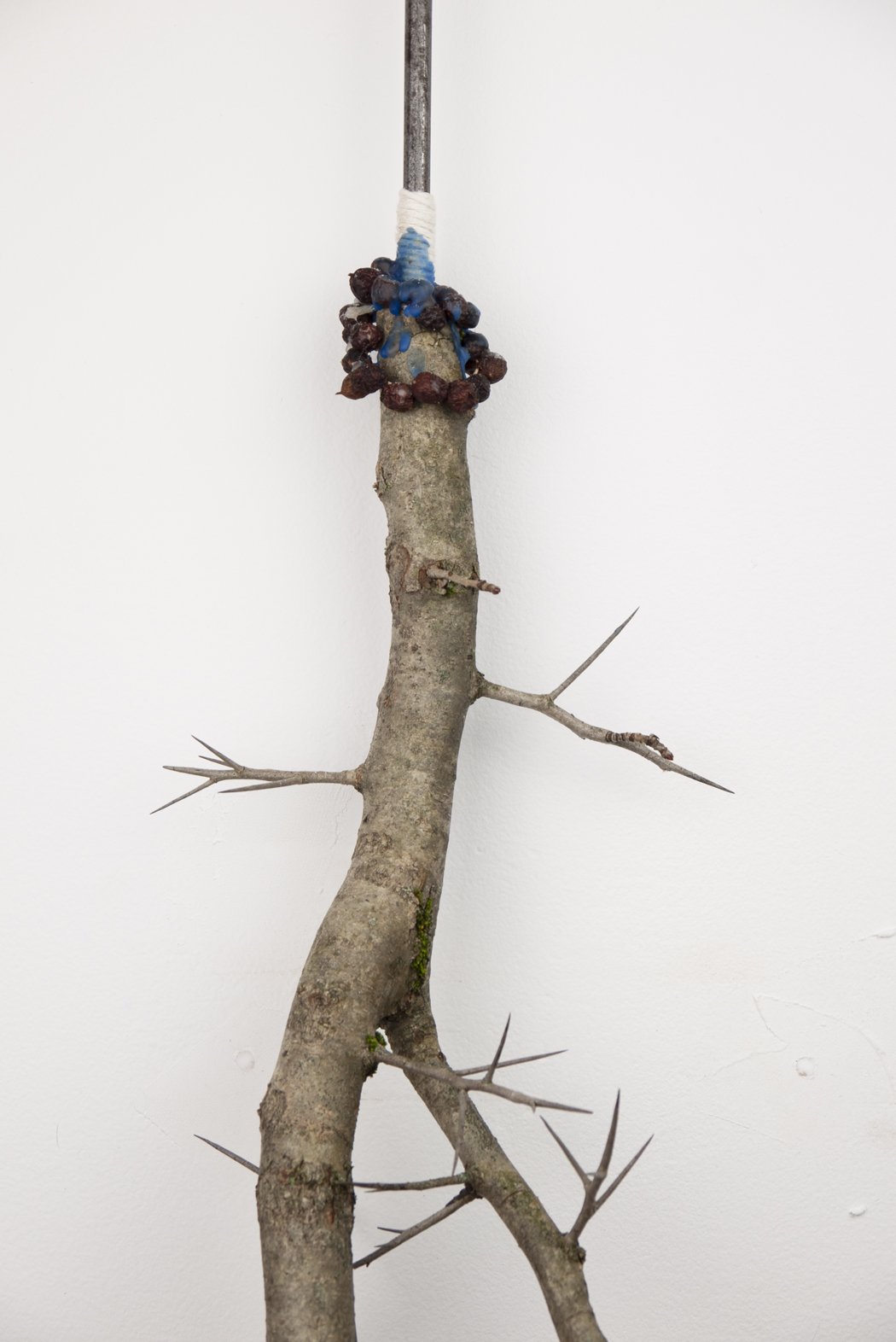

Hag

steel, hawthorn, hawthorn berries, cotton, wax

16 x 8 x 42 in.

*more information on Hag on it's individual page.

Loner is loosely based on the stories of Hekate, who is clever and a healer, who holds the torch to the way for others, and who is not domesticated and is associated with wolves, the original Lone Wolf. But also thinking about the historical loner—those who live on the edge of society either by nature or by other circumstances. I was also thinking about the loner archetype in literature or movies like in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, Jane Eyre, who’s namesake is independent and self-actualized, the title character in Toni Morrison’s Sula who is singular, intelligent, and refuses to be confined to gender or racial norms in a more prejudicial era and fiercely brillant Lisbeth Salander in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy, to name a few. I call them in.

On Rugs:

If you think of my work as a family tree, my rugs are the parents to the carpet beaters, the bells, the needle and possibly future work. The rugs represent a more of an archetypal or totemic figure—the Whore, the Crone, the Warrior, the Mother and the Heretic, to name a few.

I see rugs as objects of spatial transitions and a protective barrier—their soft borders protecting whether they are on the wall, floor or resting on one's shoulders. Keeping in mind notions of the occult, the rugs take on the motif of the magic circle which, in itself, is a boundary but it is also more than that—it is a passage, a gateway, a portal between the natural and supernatural. The rug is not necessarily used to hide something from us but to reveal the hiddenness in the world, our world—the world-in-itself vs. the world-for-us.

Hag

steel, hawthorn, hawthorn berries, cotton, wax

16 x 8 x 42 in.

Hag comes from the Greek word, hagia (ἅγιος) meaning holy woman or wise women. The earliest known use of “hag” as a derogatory word is the 13th century but was rarely used until the 16th century. The Old English word, hægtesse, once was a powerful supernatural woman thought to have carried a hawthorn branch. Hawthorn and hag have the same etymological roots and haw- the prefix of hawthorn, is related to hedge. From the online etymological dictionary I use and because I could not write it any better than their entry:

"Later, when the pagan magic was reduced to local scatterings, it might have had the sense of "hedge-rider," or "she who straddles the hedge," because the hedge was the boundary between the civilized world of the village and the wild world beyond. The hægtesse would have a foot in each reality. Even later, when it meant the local healer and root collector, living in the open and moving from village to village, it may have had the mildly pejorative Middle English sense of hedge- (hedge-priest, [hedge-witch]etc.), suggesting an itinerant sleeping under bushes. The same word could have contained all three senses before being reduced to its modern one."

By the 16th century, “hag” became a synonym for “fairy.” And in Britain, the New Year’s festival was called Hagmena—the festival by this name was first recorded in 1443 in Yorkshire but in due time, the clergyman insisted that for those who celebrated Hagmena meant they were under the devil’s influence. Today, hag denotes a cartoonishly old, poor, ugly, witchy woman who is to be afraid of. In making this carpet beater, I hope to revitalize hag and her story.

Hag

Detail

Irix

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, 23kt gold leaf

4 x 6.5 x 6 in

Irix, on the ceramic piece on the shelf is a functional bell based on the Christian demon Irix. The Christian demon Irix has associations with hawks and falcons. Because of this and its spelling, I believe it could be the demonization of the Greek Goddess Iris, the Egyptian Goddess, Isis or a mythical place in Slavic folklore called Iriy—all three have associations with hawks or birds. Ringing this bell to ring redresses this demon's origin story.

Detail with Spinster (Self)

madder dyed line, cotton and wool spun thread

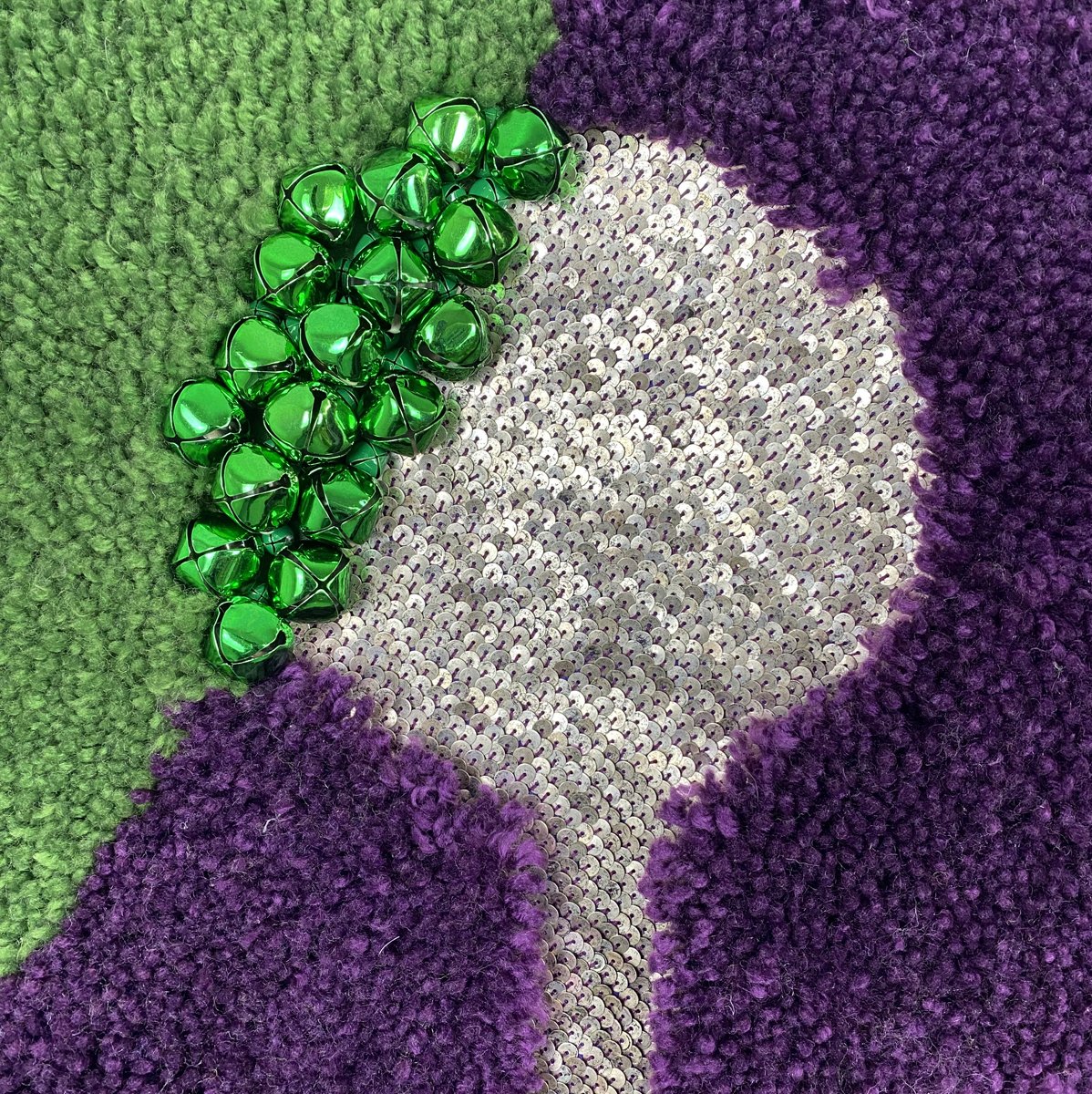

Detail of flame in Loner

In this photo, you can see other materials sewn into the rug like brass sequins and fire agate with the yarn.

Irix

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, 23kt gold leaf

4 x 6.5 x 6 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Irix is only mentioned in one grimoire, Buch Abramelin. This book was penned in German between 1387 and 1427 by Abraham von Worms. The author’s name is long thought to be a pseudonymous figure and it has been nearly conclusively proved by scholars to be the well-known 14th century Jewish scholar, Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha Levi Moellin, and more commonly known as MaHaRIL. This German book seems to be lost to time and we only know about its existence through its French translation from 1750. The 1750 translation of the text has rested virtually untouched in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in Paris until 1893, when it was stumbled upon and translated into English by the famed co-founder of The Golden Dawn, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers in 1898, renaming the book, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: As Delivered by Abraham the Jew Unto His Son Lantech.

In the French translation, Irix is merely a single word entry, its name, in a subchapter, The Servitors of Magoth and Kore from chapter 19 in the chapter, A Descriptive list of the Names of the Spirits whom We may summon to obtain that which We desire and fear. The Mathers translation goes a step further with an amendment to the chapter of his hypothesis to the meanings of each demon in Notes to the forgoing List of Names of Spirits. He suggests that the name Irix derives from Greek, hawk or falcon. Using a Greek-English dictionary from 1910 and a Greek Lexicon with words from the Roman era published in 1914, I could not corroborate Mathers’ translation.

However, since I am not fluent in Greek or ancient Greek or anything really, I am going to go with Mathers’ hawk or falcon suggestion. In using that limited framework, clearly Irix derivative of Isis, the Egyptian goddess of healing and magic, and Iris, in Greek mythology, she is the personification of a rainbow, the halo to the moon and the messenger of the gods and possibly, a little known mythical place in Slavic folklore called Iriy where “birds fly for the winter and souls go after death.” Isis and Iris are goddesses described and commonly depicted with bird-like wings and Iriy, a place associated with birds and death.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Irix and Isis, Iris, and the neitherworld, Iriy, is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me it is too obvious of a connection if relying on Mather’s translation. It still surprises me how demonic scholars and modern occultists have no problem correlating popular Roman and Greek gods and goddesses to demons but seem to not even scratch the surface of more obscure demons and their mythological origins even when they are so similar in spelling and description.

Other (rug)

yarn, wool, steel and other diverse things.

6' x 7' x 8"

2024

My rugs call on archetypal identities. The rug in this grouping is called Other. This rug can be worn like a jacket. The rug hugs those who are othered and brings inside those who are out.

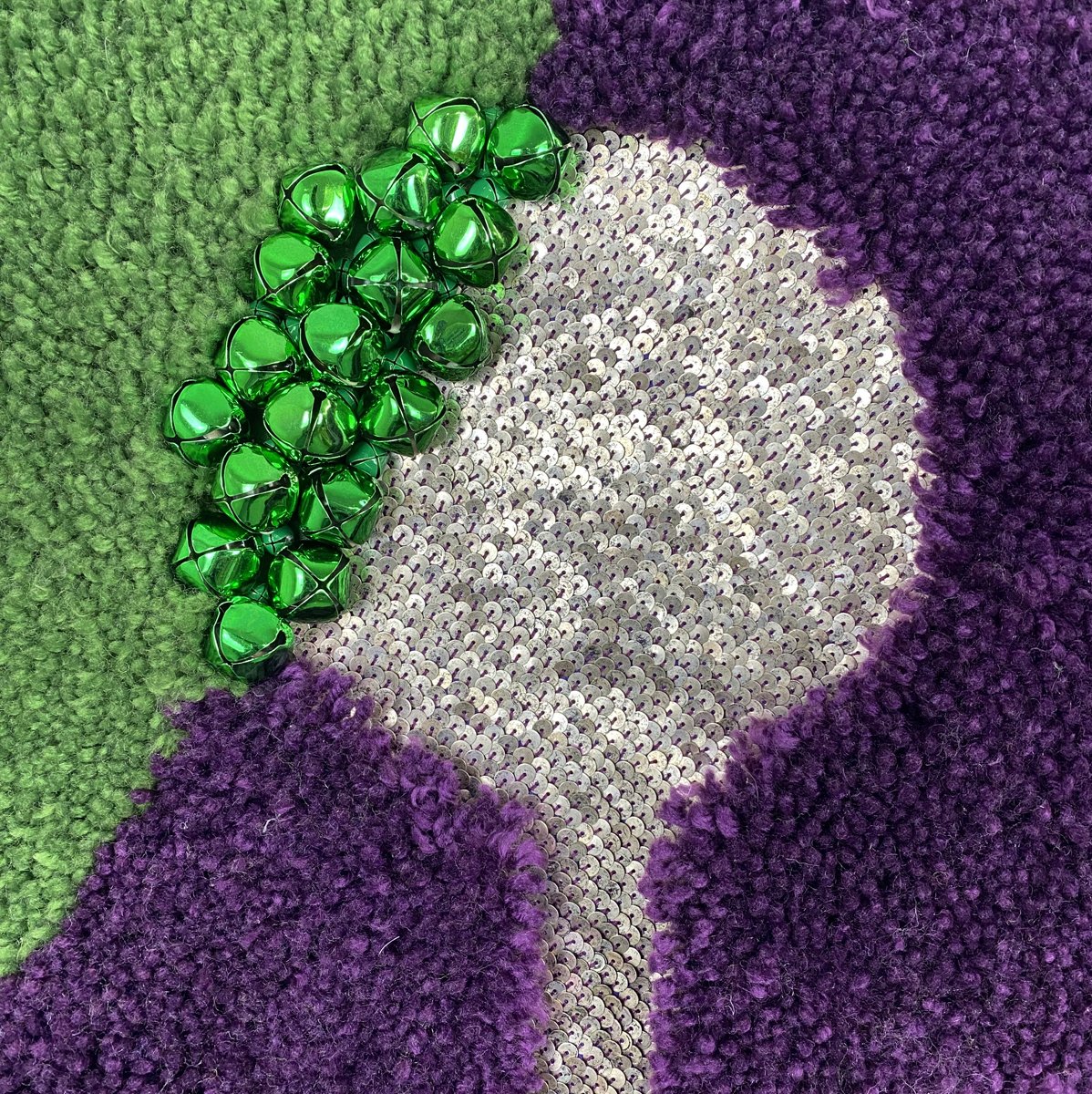

Detail of Other

In this photo, you can see other materials sewn into the rug like recycled tin sequins, aluminum bells with the yarn.

Baal

steel, goat foot, wood, hemp, burlap, red ochre

42 x 12 x 5 in.

2023

The top carpet beater is named after the ancient Canaanite God of fertility, Baal and considered one of the most important gods of that time. During this same time period, baal was used as an honorific like “lord” and “owner.” With the rise of monotheistic religions, Baal became a Christian and Hebrew demon, Baal, demonized and is the root word for the famed demon, Beelzebub.

Styrax

steel, wood, black storax

43 x 14 x 7 in.

2023

The bottom carpet beater is for the demon 'Styrax' which could be the demonization of the resin storax which was used in protective folk magic and as ink in occult writing dating as far back as the medieval period in European history. Using the carpet beaters to clean the rug redresses these demons' origin story.

The dagger to the left of Styrax is a damascus steel blade with a roe deer antler that has been handled by hands covered with white caulk paint. This dagger was make in collaboration with a bladesmith, Nick Anger.

Detail of Styrax

Klothod

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

9.5 x 6 x 10 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Before I got into demons, I was into goddesses and particularly groups of goddesses like The Moirai, the Norns, the Parcae, and the Pleiades. For this demon, the Fates in Greek mythology are the point of interest. They are Clotho, also spelled Klotho, who spins the thread for a person’s life and her sisters, Lachesis, who sews or weaves that person’s life and Atropos, who cuts the thread causing death in that life.

There is also a demon named Klothod. The earliest found reference to Klothod, the demon, is in the Testament of Solomon. This text only exists day through its copies and translations but it is believed by scholars that the Testament could have been begun as early as the 1st century ADE and finished sometime in the Middle Ages. I used three different translations of the text. In two of the translations, one from author F.C. Conybeare from the Jewish Quarterly Review, 1898 and the other, D.C. Duling’s translation, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1983, Klothod is mentioned as their name—“The Third: I am Klothod, which is battle.” Whereas in the other text, the James Charlesworth translation, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha from 1999, Klothod is not mentioned by name but as Fate—“The third said, “I am called Fate. I cause every man to fight in battle rather than make peace honorably with those who are winning.”

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. I find it notable that contemporary demonologists, occultists and scholar’s have not linked Klothod the demon to Klotho or Clotho of the Three Fates in Greek mythology. The similarities are obvious.

Gemory

underglaze on stoneware, 23kt gold leaf, waxed thread

4.5 x 6.5 x 5.5 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo

A few grimoires of the period mention Gemory, also spelled Gremory and Gomory. The first found recording of Gemory is in Johann Weyer’s Praestigiis Daemonum (1563). This book is a rebuttal of sorts against the hateful witch hunter's handbook, Malleus Maleficarum (1487), by Heinrich Kramer. Using Joseph Peterson’s translation from 2000, Gemory is a strong and mighty duke that appears as a fair woman, wearing a crown and riding a camel. They have the ability to see the past, present and future, find hidden treasure and can procure the love of women. Gemory used he/him pronouns. Gemory is also mentioned with little alteration in Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) except to include that Gemory is considered a fiend—as in an Incubus and Succubus and could be of either sex. They are also mentioned in the Goetia of Dr. Rudd is also known as Goetia:The Lesser Key of Solomon. The earliest known copy of the Goetia of Dr. Rudd from 1641 but contemporary occult scholars believe that this copy of an older book about 350 to 400 years earlier.

The demon, Gemory, is a part of the group of demons I call: The Demons I Want on my Team, for lack of a more catchy title. Sometimes there is just nothing to tie the demon to anything but a larger historical discriminatory practice or trend, like the demonization of homosexuality in Christian Europe. Years ago I came across this scholarly essay, “The Demons' Reaction to Sodomy: Witchcraft and Homosexuality in Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola's "Strix" by Tamar Herzig in The Sixteenth Century Journal. The essay lays out specifically the demonization of homosexuals in sixteenth century Italy. She lays out how medieval theologians stressed demons’ disgust at sodomy but by the fifteenth century, theologians of the time began to connect sodomy and homosexuality with the expanding crime of witchcraft. By the sixteenth century, demons were homosexuals and homosexuals were demons. This transition in views began to shape some demons’ characteristics in writings of the time to resemble how queer culture of the European Middle Ages shamed, vilified and criminalized that community. Gemory, Gomory, Gremory is the sixteenth century demonization of the Other—the Other being a cross-dressing, drag, queer and/or trans person/s.

Carnax

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

6 x 4 x 8.5 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Sometimes a demon is not the villainization of a person or deity but of a tool of war held by the enemy, the Other—in this case, the Other being the Celts and the Gauls. In war, these tribes would use a Iron Age battle horn called the carnyx to bellow a scream that struck fear when heard by the Romans and later, the Christians. The carnyx was as tall as a person with an animal shaped head, often a boar but a dragon, stag or bull’s head have been found. It was intended to inspire soldiers and terrify enemies on the battlefield. It was also used as a festive instrument on high holidays and there are references to this particular horn during the Iron Ages as far as Egypt, Turkmenistan and India. At archaeological sites, carnyxes have been found as far as Eurasia.

There is also a demon named Carnax, also spelled Carmox. The demon first appears in Liber juratus Honorii, . a medieval grimoire supposedly written either by Honorius of Thebes, son of Euclid—who scholars presumed to be mythical—or by Pope Honorius I of the seventh century ADE. The date of this composition is uncertain but the first certain historical record is the 1347 trial record of Étienne Pépin from Mende, Gévaudan, in the Kingdoms of France and Navarre. Additionally, Johannes Hartlieb (1456), physician of Late Medieval Bavaria, mentions it as one of the books used in necromancy. The oldest preserved manuscript dates to the 14th century and is currently housed in the British Library. The first printed publication of this manuscript did not appear until 1629.

In the two English translations I found, one by the Daniel Driscoll’s and the other Joseph Peterson (1998), Carnax is similarly described as Their nature is to cause war, and plague, murder, treason, and burnings; they also temporarily give one thousand soldiers with their servants, which are two thousand, and they grant death; they also grant sickness or health to anyone. These is also a physical description given—horns like a stag, nails like a griffin with a howl like a mad bull. One thing is clear in each translation, Carnax is a demon for war. From my research into debunking “real” demons, it is not surprising that the ancient war horn and festival instrument, the carnyx, used by the Celts and Gauls was demonized by Christains.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Carnax with carnyx is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me it is too obvious of a connection and I have yet to find any occult scholars or modern demonologists comparing or equating the two but to me. I ring this bell, Carnax, to redress this possibly lost history and connection.

Ischiron

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

6 x 4 x 6 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Ischiron was first identified in the magickal book, Buch Abramelin, penned in German between 1387 and 1427 by Abraham von Worms. The author’s name is long thought to be a pseudonymous figure and it has been nearly conclusively proved by scholars to be the well-known 14th century Jewish scholar, Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha Levi Moellin, and more commonly known as MaHaRIL. This German book seems to be lost to time and we only know about its existence through its French translation from 1750. The 1750 translation rested virtually untouched in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in Paris until 1893, when it was stumbled upon and translated into English by the famed co-founder of The Golden Dawn, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers. He published the translation in 1898, renaming the book, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: As Delivered by Abraham the Jew Unto His Son Lantech.

In the French translation, Ischiron is merely a single word entry, its name, in a subchapter, The Servitors of Magoth and Kore from chapter 19 in the chapter, A Descriptive list of the Names of the Spirits whom We may summon to obtain that which We desire and fear. The Mathers translation goes a step further with an amendment to the chapter of his hypothesis to the meanings of each demon in Notes to the forgoing List of Names of Spirits. He suggests that the name Ischiron derives from Greek meaning strong or mighty.

From my translations: Ισχυρων (Greek)= Ischyron (Greek in latized letters) = strong ones (English translation) and ισχυρός (Greek) = Ischyrós Greek in latized letters) = mighty (English translation). I lay out my translations because in the past (reference the demon Irix) I could not substantiate Mathers translation where with “Ischiron,” I could.

Ischiron is also referenced in the Elizabethan grimoire, The Book of Oberon (1577), author/s unknown, and is spelled Ischiros here. In my opinion, this text comes across as an heretical Christian text using demons, angels and faeries for conjuring and prayers. Using the 2015 translation by Daniel Harms, James R. Clark, and Joseph H. Peterson, little is mentioned about Ischiron themselves but Ischiron is named as a protector of sorts. From a prayer in The Book of Oberon:

Prayers against all worldly dangers

The apostle Saint Thomas and Leonard 30 wrote to Charles, king of France, saying: "Whoever wears these names on himself cannot be harmed by their mortal enemies, nor will he be able to harm them. And note, this writing contains a name Agla, a name of Christ, and it is said that whoever sees, speaks, or carries it, will not die an evil death that day, and if any sick person wears it around their neck, they will enjoy health, and a pregnant woman who ties it over her stomach will be free of pain. (p.64)

It continues with a long list of names that include the Father, Son and Holy Ghost to a listing of earthly elements and Ischrios with the footnote by the authors of the 2015 translation, Ischrios: Gk. “mighty”.

Now in Greek Mythology, there is a very important and the most famous centaur named Chiron who is the son of the Titan, Cronus and the Oceanid, Philyra. Unlike other Centaurs who were violent and savage, Chiron was renowned for his wisdom, knowledge of medicine, strength and bravery. Many Greek heroes were tutored by him including Achilles, Aeson and Hercules to name a few. And to make a long Greek story short, Chiron was immortal through his father, Cronus. Chiron relinquished his immortality to save Prometheus from a prolonged tortured imprisonment for the crime of giving humans fire. Zeus, taking pity on Chiron's sacrifice, decided to honor him by immortalizing him in the constellation Centaurus. The earliest found recording of this constellation is by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Before the spread of Christianity, Chiron was invoked to aid with divinations, athletics, tutoring, nursing and healing, hunting, music, the sciences, literature, everything wise. Chiron was mighty and strong.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Ischiron and Ischiros with Chiron is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me, the connection is clear. It surprises me how demonic scholars and modern occultists have no problem correlating popular Roman and Greek gods and goddesses to demons but seem to not even scratch the surface of more obscure demons and their mythological origins even when they are an established western named constellation.

Kobal

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, recycled glass beads

6 x 7 x 8 in

Video of the bell's ringing can be found on Vimeo

From several grimoires and magical books, the demon Kobal is also known as the “Masters of the Revels.” In my research, Kobal could be the demonization of kobaloi who were mischievous sprites from Greek mythology.

Or and could be related to the Kobold from German folklore, a sprite-like goblin and hobgoblin.* More interestingly, Kobal, kobaloi, and kobold could be a root word for the element, cobalt. Chemistry professor Allan Blackman, from Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand labeled cobalt “the goblin of the periodic table.” From his writing, Cobalt, a metal-like ore, was found and named Kobold by miners in 16th century Saxony who thought they found deposits of silver but actually found cobalt arsenide. It was “discovered” by science by Georg Brandt in 1739.

Cobalt, the element is toxic to humans. Studies have shown that the risk of birth defects, such as limb abnormalities and spina bifida, greatly increased when a parent worked in a cobalt mine along with causing cancer. Sixteenth century science knew little to nothing about cobalt and the health effects. After mining cobalt over a short period of time, the miners probably quickly knew something was wrong health-wise but did not have the knowledge to understand that their work was causing their illness in their homes. Blaming their homes over work for their woes, created the house goblin, colloquially called Kobold or Kobal. In turn, decades later having these miners introduce this “rock” to Brandt, he kept the name Cobalt.

*A hobgoblin is a mischievous house imp or sprite.

Spinster (I wish, I want, I will, I must)

strips of clothing, steel

5.5ft x 6ft x 2ft

Me, the spinster—an unmarried childless person. But also, the word, spinster, originally a neutral term for a tradeswoman’s occupation originating in the mid-1300s meaning ‘a woman who spins for a living” and who could make a living without having a husband or father. And the demon Klothod, first identified in text from the third century ADE, who is the demonization of the goddess Clotho, one of the three Fates in Greek mythology, who spins the thread of one’s life, therefore, a spinster.

On the Spinster series:

In the past year, I have been forging large steel sewing needle-like sculptures and hand twisting rope that, in a sense, functions as thread. The needle lends itself to be a drawing tool leaving the thread as its mark. This work writes as drawing and draws as sculpture with the title of each wall drawing functioning as the key to its language.

Spinster (I gave birth, but did not bring a child to life)

strips of clothing, steel

90 x 96 x 24in.

“I was pregnant, but unable to bring my child to term; I gave birth, but did not bring a child to life. May a woman who grants me success release me. May I have a straightforward pregnancy.” is part of a larger incantation written in cuneiform on a tablet from Mesopotamia—roughly 2000-1500 BCE. This incantation is part of a set of directions on how to banish the Mesopotamian demon, Lamashtu, eater of fetuses and killer of mothers and have a healthy child and survive pregnancy.

This incantation reverberates through the millennia to today in the United States and many parts of the world where theological laws supersedes medical advancements in Obstetrics. I draw these words with my needle and thread for pregnant people.

Spinster (I saw with my own eyes)

strips of clothing, steel

70 x 90 x 20 in.

One of my favorite books that I have read or listened to over and over again is Michael Crichton’s Eater of the Dead which lead me to read the English translation of Ahmad ibn Fadlan’s Risala, the personal account of his journey north into Volga Viking territory from his home, Baghdad, in the 10th century—Crichton book is more of a loose translation with some literary devices to make ibn Fadlan’s account read more like a novel. But in many of Crichton’s scenes that use ibn Fadlan words, there are no major edits.

In saying all of that, this piece is not about this favored story but more about the repetitive “I saw…” statements in the translation and novel, specifically “I saw with my own eyes” and “I saw nothing with my own eyes.” And reflecting thru drawing how that seeing and witnessing is recorded and biases cast. In much of this years work, I think about how the past connects us with the present to remember how we tell our stories for the future.

Loner with Hag, Irix and Spinster (Self)

Loner

yarn, snake skin, faux snake skin, cow leather with hide, brass, fire agate, waxed thread, steel grommets, iron oxide stained oak

51" x 4" x 62"

Hag

steel, hawthorn, hawthorn berries, cotton, wax

16 x 8 x 42 in.

*more information on Hag on it's individual page.

Loner is loosely based on the stories of Hekate, who is clever and a healer, who holds the torch to the way for others, and who is not domesticated and is associated with wolves, the original Lone Wolf. But also thinking about the historical loner—those who live on the edge of society either by nature or by other circumstances. I was also thinking about the loner archetype in literature or movies like in Charlotte Bronte’s novel, Jane Eyre, who’s namesake is independent and self-actualized, the title character in Toni Morrison’s Sula who is singular, intelligent, and refuses to be confined to gender or racial norms in a more prejudicial era and fiercely brillant Lisbeth Salander in The Girl With the Dragon Tattoo Trilogy, to name a few. I call them in.

On Rugs:

If you think of my work as a family tree, my rugs are the parents to the carpet beaters, the bells, the needle and possibly future work. The rugs represent a more of an archetypal or totemic figure—the Whore, the Crone, the Warrior, the Mother and the Heretic, to name a few.

I see rugs as objects of spatial transitions and a protective barrier—their soft borders protecting whether they are on the wall, floor or resting on one's shoulders. Keeping in mind notions of the occult, the rugs take on the motif of the magic circle which, in itself, is a boundary but it is also more than that—it is a passage, a gateway, a portal between the natural and supernatural. The rug is not necessarily used to hide something from us but to reveal the hiddenness in the world, our world—the world-in-itself vs. the world-for-us.

Hag

steel, hawthorn, hawthorn berries, cotton, wax

16 x 8 x 42 in.

Hag comes from the Greek word, hagia (ἅγιος) meaning holy woman or wise women. The earliest known use of “hag” as a derogatory word is the 13th century but was rarely used until the 16th century. The Old English word, hægtesse, once was a powerful supernatural woman thought to have carried a hawthorn branch. Hawthorn and hag have the same etymological roots and haw- the prefix of hawthorn, is related to hedge. From the online etymological dictionary I use and because I could not write it any better than their entry:

"Later, when the pagan magic was reduced to local scatterings, it might have had the sense of "hedge-rider," or "she who straddles the hedge," because the hedge was the boundary between the civilized world of the village and the wild world beyond. The hægtesse would have a foot in each reality. Even later, when it meant the local healer and root collector, living in the open and moving from village to village, it may have had the mildly pejorative Middle English sense of hedge- (hedge-priest, [hedge-witch]etc.), suggesting an itinerant sleeping under bushes. The same word could have contained all three senses before being reduced to its modern one."

By the 16th century, “hag” became a synonym for “fairy.” And in Britain, the New Year’s festival was called Hagmena—the festival by this name was first recorded in 1443 in Yorkshire but in due time, the clergyman insisted that for those who celebrated Hagmena meant they were under the devil’s influence. Today, hag denotes a cartoonishly old, poor, ugly, witchy woman who is to be afraid of. In making this carpet beater, I hope to revitalize hag and her story.

Hag

Detail

Irix

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, 23kt gold leaf

4 x 6.5 x 6 in

Irix, on the ceramic piece on the shelf is a functional bell based on the Christian demon Irix. The Christian demon Irix has associations with hawks and falcons. Because of this and its spelling, I believe it could be the demonization of the Greek Goddess Iris, the Egyptian Goddess, Isis or a mythical place in Slavic folklore called Iriy—all three have associations with hawks or birds. Ringing this bell to ring redresses this demon's origin story.

Detail with Spinster (Self)

madder dyed line, cotton and wool spun thread

Detail of flame in Loner

In this photo, you can see other materials sewn into the rug like brass sequins and fire agate with the yarn.

Irix

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, 23kt gold leaf

4 x 6.5 x 6 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Irix is only mentioned in one grimoire, Buch Abramelin. This book was penned in German between 1387 and 1427 by Abraham von Worms. The author’s name is long thought to be a pseudonymous figure and it has been nearly conclusively proved by scholars to be the well-known 14th century Jewish scholar, Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha Levi Moellin, and more commonly known as MaHaRIL. This German book seems to be lost to time and we only know about its existence through its French translation from 1750. The 1750 translation of the text has rested virtually untouched in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in Paris until 1893, when it was stumbled upon and translated into English by the famed co-founder of The Golden Dawn, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers in 1898, renaming the book, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: As Delivered by Abraham the Jew Unto His Son Lantech.

In the French translation, Irix is merely a single word entry, its name, in a subchapter, The Servitors of Magoth and Kore from chapter 19 in the chapter, A Descriptive list of the Names of the Spirits whom We may summon to obtain that which We desire and fear. The Mathers translation goes a step further with an amendment to the chapter of his hypothesis to the meanings of each demon in Notes to the forgoing List of Names of Spirits. He suggests that the name Irix derives from Greek, hawk or falcon. Using a Greek-English dictionary from 1910 and a Greek Lexicon with words from the Roman era published in 1914, I could not corroborate Mathers’ translation.

However, since I am not fluent in Greek or ancient Greek or anything really, I am going to go with Mathers’ hawk or falcon suggestion. In using that limited framework, clearly Irix derivative of Isis, the Egyptian goddess of healing and magic, and Iris, in Greek mythology, she is the personification of a rainbow, the halo to the moon and the messenger of the gods and possibly, a little known mythical place in Slavic folklore called Iriy where “birds fly for the winter and souls go after death.” Isis and Iris are goddesses described and commonly depicted with bird-like wings and Iriy, a place associated with birds and death.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Irix and Isis, Iris, and the neitherworld, Iriy, is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me it is too obvious of a connection if relying on Mather’s translation. It still surprises me how demonic scholars and modern occultists have no problem correlating popular Roman and Greek gods and goddesses to demons but seem to not even scratch the surface of more obscure demons and their mythological origins even when they are so similar in spelling and description.

Other (rug)

yarn, wool, steel and other diverse things.

6' x 7' x 8"

2024

My rugs call on archetypal identities. The rug in this grouping is called Other. This rug can be worn like a jacket. The rug hugs those who are othered and brings inside those who are out.

Detail of Other

In this photo, you can see other materials sewn into the rug like recycled tin sequins, aluminum bells with the yarn.

Baal

steel, goat foot, wood, hemp, burlap, red ochre

42 x 12 x 5 in.

2023

The top carpet beater is named after the ancient Canaanite God of fertility, Baal and considered one of the most important gods of that time. During this same time period, baal was used as an honorific like “lord” and “owner.” With the rise of monotheistic religions, Baal became a Christian and Hebrew demon, Baal, demonized and is the root word for the famed demon, Beelzebub.

Styrax

steel, wood, black storax

43 x 14 x 7 in.

2023

The bottom carpet beater is for the demon 'Styrax' which could be the demonization of the resin storax which was used in protective folk magic and as ink in occult writing dating as far back as the medieval period in European history. Using the carpet beaters to clean the rug redresses these demons' origin story.

The dagger to the left of Styrax is a damascus steel blade with a roe deer antler that has been handled by hands covered with white caulk paint. This dagger was make in collaboration with a bladesmith, Nick Anger.

Detail of Styrax

Klothod

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

9.5 x 6 x 10 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Before I got into demons, I was into goddesses and particularly groups of goddesses like The Moirai, the Norns, the Parcae, and the Pleiades. For this demon, the Fates in Greek mythology are the point of interest. They are Clotho, also spelled Klotho, who spins the thread for a person’s life and her sisters, Lachesis, who sews or weaves that person’s life and Atropos, who cuts the thread causing death in that life.

There is also a demon named Klothod. The earliest found reference to Klothod, the demon, is in the Testament of Solomon. This text only exists day through its copies and translations but it is believed by scholars that the Testament could have been begun as early as the 1st century ADE and finished sometime in the Middle Ages. I used three different translations of the text. In two of the translations, one from author F.C. Conybeare from the Jewish Quarterly Review, 1898 and the other, D.C. Duling’s translation, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha, 1983, Klothod is mentioned as their name—“The Third: I am Klothod, which is battle.” Whereas in the other text, the James Charlesworth translation, The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha from 1999, Klothod is not mentioned by name but as Fate—“The third said, “I am called Fate. I cause every man to fight in battle rather than make peace honorably with those who are winning.”

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. I find it notable that contemporary demonologists, occultists and scholar’s have not linked Klothod the demon to Klotho or Clotho of the Three Fates in Greek mythology. The similarities are obvious.

Gemory

underglaze on stoneware, 23kt gold leaf, waxed thread

4.5 x 6.5 x 5.5 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo

A few grimoires of the period mention Gemory, also spelled Gremory and Gomory. The first found recording of Gemory is in Johann Weyer’s Praestigiis Daemonum (1563). This book is a rebuttal of sorts against the hateful witch hunter's handbook, Malleus Maleficarum (1487), by Heinrich Kramer. Using Joseph Peterson’s translation from 2000, Gemory is a strong and mighty duke that appears as a fair woman, wearing a crown and riding a camel. They have the ability to see the past, present and future, find hidden treasure and can procure the love of women. Gemory used he/him pronouns. Gemory is also mentioned with little alteration in Reginald Scot’s The Discoverie of Witchcraft (1584) except to include that Gemory is considered a fiend—as in an Incubus and Succubus and could be of either sex. They are also mentioned in the Goetia of Dr. Rudd is also known as Goetia:The Lesser Key of Solomon. The earliest known copy of the Goetia of Dr. Rudd from 1641 but contemporary occult scholars believe that this copy of an older book about 350 to 400 years earlier.

The demon, Gemory, is a part of the group of demons I call: The Demons I Want on my Team, for lack of a more catchy title. Sometimes there is just nothing to tie the demon to anything but a larger historical discriminatory practice or trend, like the demonization of homosexuality in Christian Europe. Years ago I came across this scholarly essay, “The Demons' Reaction to Sodomy: Witchcraft and Homosexuality in Gianfrancesco Pico della Mirandola's "Strix" by Tamar Herzig in The Sixteenth Century Journal. The essay lays out specifically the demonization of homosexuals in sixteenth century Italy. She lays out how medieval theologians stressed demons’ disgust at sodomy but by the fifteenth century, theologians of the time began to connect sodomy and homosexuality with the expanding crime of witchcraft. By the sixteenth century, demons were homosexuals and homosexuals were demons. This transition in views began to shape some demons’ characteristics in writings of the time to resemble how queer culture of the European Middle Ages shamed, vilified and criminalized that community. Gemory, Gomory, Gremory is the sixteenth century demonization of the Other—the Other being a cross-dressing, drag, queer and/or trans person/s.

Carnax

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

6 x 4 x 8.5 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Sometimes a demon is not the villainization of a person or deity but of a tool of war held by the enemy, the Other—in this case, the Other being the Celts and the Gauls. In war, these tribes would use a Iron Age battle horn called the carnyx to bellow a scream that struck fear when heard by the Romans and later, the Christians. The carnyx was as tall as a person with an animal shaped head, often a boar but a dragon, stag or bull’s head have been found. It was intended to inspire soldiers and terrify enemies on the battlefield. It was also used as a festive instrument on high holidays and there are references to this particular horn during the Iron Ages as far as Egypt, Turkmenistan and India. At archaeological sites, carnyxes have been found as far as Eurasia.

There is also a demon named Carnax, also spelled Carmox. The demon first appears in Liber juratus Honorii, . a medieval grimoire supposedly written either by Honorius of Thebes, son of Euclid—who scholars presumed to be mythical—or by Pope Honorius I of the seventh century ADE. The date of this composition is uncertain but the first certain historical record is the 1347 trial record of Étienne Pépin from Mende, Gévaudan, in the Kingdoms of France and Navarre. Additionally, Johannes Hartlieb (1456), physician of Late Medieval Bavaria, mentions it as one of the books used in necromancy. The oldest preserved manuscript dates to the 14th century and is currently housed in the British Library. The first printed publication of this manuscript did not appear until 1629.

In the two English translations I found, one by the Daniel Driscoll’s and the other Joseph Peterson (1998), Carnax is similarly described as Their nature is to cause war, and plague, murder, treason, and burnings; they also temporarily give one thousand soldiers with their servants, which are two thousand, and they grant death; they also grant sickness or health to anyone. These is also a physical description given—horns like a stag, nails like a griffin with a howl like a mad bull. One thing is clear in each translation, Carnax is a demon for war. From my research into debunking “real” demons, it is not surprising that the ancient war horn and festival instrument, the carnyx, used by the Celts and Gauls was demonized by Christains.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Carnax with carnyx is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me it is too obvious of a connection and I have yet to find any occult scholars or modern demonologists comparing or equating the two but to me. I ring this bell, Carnax, to redress this possibly lost history and connection.

Ischiron

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread

6 x 4 x 6 in

Video of the bell ringing can be found on Vimeo.

Ischiron was first identified in the magickal book, Buch Abramelin, penned in German between 1387 and 1427 by Abraham von Worms. The author’s name is long thought to be a pseudonymous figure and it has been nearly conclusively proved by scholars to be the well-known 14th century Jewish scholar, Rabbi Jacob ben Moses ha Levi Moellin, and more commonly known as MaHaRIL. This German book seems to be lost to time and we only know about its existence through its French translation from 1750. The 1750 translation rested virtually untouched in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal in Paris until 1893, when it was stumbled upon and translated into English by the famed co-founder of The Golden Dawn, Samuel Liddell MacGregor Mathers. He published the translation in 1898, renaming the book, The Sacred Magic of Abramelin the Mage: As Delivered by Abraham the Jew Unto His Son Lantech.

In the French translation, Ischiron is merely a single word entry, its name, in a subchapter, The Servitors of Magoth and Kore from chapter 19 in the chapter, A Descriptive list of the Names of the Spirits whom We may summon to obtain that which We desire and fear. The Mathers translation goes a step further with an amendment to the chapter of his hypothesis to the meanings of each demon in Notes to the forgoing List of Names of Spirits. He suggests that the name Ischiron derives from Greek meaning strong or mighty.

From my translations: Ισχυρων (Greek)= Ischyron (Greek in latized letters) = strong ones (English translation) and ισχυρός (Greek) = Ischyrós Greek in latized letters) = mighty (English translation). I lay out my translations because in the past (reference the demon Irix) I could not substantiate Mathers translation where with “Ischiron,” I could.

Ischiron is also referenced in the Elizabethan grimoire, The Book of Oberon (1577), author/s unknown, and is spelled Ischiros here. In my opinion, this text comes across as an heretical Christian text using demons, angels and faeries for conjuring and prayers. Using the 2015 translation by Daniel Harms, James R. Clark, and Joseph H. Peterson, little is mentioned about Ischiron themselves but Ischiron is named as a protector of sorts. From a prayer in The Book of Oberon:

Prayers against all worldly dangers

The apostle Saint Thomas and Leonard 30 wrote to Charles, king of France, saying: "Whoever wears these names on himself cannot be harmed by their mortal enemies, nor will he be able to harm them. And note, this writing contains a name Agla, a name of Christ, and it is said that whoever sees, speaks, or carries it, will not die an evil death that day, and if any sick person wears it around their neck, they will enjoy health, and a pregnant woman who ties it over her stomach will be free of pain. (p.64)

It continues with a long list of names that include the Father, Son and Holy Ghost to a listing of earthly elements and Ischrios with the footnote by the authors of the 2015 translation, Ischrios: Gk. “mighty”.

Now in Greek Mythology, there is a very important and the most famous centaur named Chiron who is the son of the Titan, Cronus and the Oceanid, Philyra. Unlike other Centaurs who were violent and savage, Chiron was renowned for his wisdom, knowledge of medicine, strength and bravery. Many Greek heroes were tutored by him including Achilles, Aeson and Hercules to name a few. And to make a long Greek story short, Chiron was immortal through his father, Cronus. Chiron relinquished his immortality to save Prometheus from a prolonged tortured imprisonment for the crime of giving humans fire. Zeus, taking pity on Chiron's sacrifice, decided to honor him by immortalizing him in the constellation Centaurus. The earliest found recording of this constellation is by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy. Before the spread of Christianity, Chiron was invoked to aid with divinations, athletics, tutoring, nursing and healing, hunting, music, the sciences, literature, everything wise. Chiron was mighty and strong.

I am not a scholar on any histories, the occult, or demonology. I am an artist who tries to think outside the box of accepted research. This correlation between Ischiron and Ischiros with Chiron is only speculative on my part. Albeit, to me, the connection is clear. It surprises me how demonic scholars and modern occultists have no problem correlating popular Roman and Greek gods and goddesses to demons but seem to not even scratch the surface of more obscure demons and their mythological origins even when they are an established western named constellation.

Kobal

underglaze on stoneware, waxed thread, recycled glass beads

6 x 7 x 8 in

Video of the bell's ringing can be found on Vimeo

From several grimoires and magical books, the demon Kobal is also known as the “Masters of the Revels.” In my research, Kobal could be the demonization of kobaloi who were mischievous sprites from Greek mythology.

Or and could be related to the Kobold from German folklore, a sprite-like goblin and hobgoblin.* More interestingly, Kobal, kobaloi, and kobold could be a root word for the element, cobalt. Chemistry professor Allan Blackman, from Auckland University of Technology in New Zealand labeled cobalt “the goblin of the periodic table.” From his writing, Cobalt, a metal-like ore, was found and named Kobold by miners in 16th century Saxony who thought they found deposits of silver but actually found cobalt arsenide. It was “discovered” by science by Georg Brandt in 1739.

Cobalt, the element is toxic to humans. Studies have shown that the risk of birth defects, such as limb abnormalities and spina bifida, greatly increased when a parent worked in a cobalt mine along with causing cancer. Sixteenth century science knew little to nothing about cobalt and the health effects. After mining cobalt over a short period of time, the miners probably quickly knew something was wrong health-wise but did not have the knowledge to understand that their work was causing their illness in their homes. Blaming their homes over work for their woes, created the house goblin, colloquially called Kobold or Kobal. In turn, decades later having these miners introduce this “rock” to Brandt, he kept the name Cobalt.

*A hobgoblin is a mischievous house imp or sprite.

Spinster (I wish, I want, I will, I must)

strips of clothing, steel

5.5ft x 6ft x 2ft

Me, the spinster—an unmarried childless person. But also, the word, spinster, originally a neutral term for a tradeswoman’s occupation originating in the mid-1300s meaning ‘a woman who spins for a living” and who could make a living without having a husband or father. And the demon Klothod, first identified in text from the third century ADE, who is the demonization of the goddess Clotho, one of the three Fates in Greek mythology, who spins the thread of one’s life, therefore, a spinster.

On the Spinster series:

In the past year, I have been forging large steel sewing needle-like sculptures and hand twisting rope that, in a sense, functions as thread. The needle lends itself to be a drawing tool leaving the thread as its mark. This work writes as drawing and draws as sculpture with the title of each wall drawing functioning as the key to its language.

Spinster (I gave birth, but did not bring a child to life)

strips of clothing, steel

90 x 96 x 24in.

“I was pregnant, but unable to bring my child to term; I gave birth, but did not bring a child to life. May a woman who grants me success release me. May I have a straightforward pregnancy.” is part of a larger incantation written in cuneiform on a tablet from Mesopotamia—roughly 2000-1500 BCE. This incantation is part of a set of directions on how to banish the Mesopotamian demon, Lamashtu, eater of fetuses and killer of mothers and have a healthy child and survive pregnancy.

This incantation reverberates through the millennia to today in the United States and many parts of the world where theological laws supersedes medical advancements in Obstetrics. I draw these words with my needle and thread for pregnant people.

Spinster (I saw with my own eyes)

strips of clothing, steel

70 x 90 x 20 in.

One of my favorite books that I have read or listened to over and over again is Michael Crichton’s Eater of the Dead which lead me to read the English translation of Ahmad ibn Fadlan’s Risala, the personal account of his journey north into Volga Viking territory from his home, Baghdad, in the 10th century—Crichton book is more of a loose translation with some literary devices to make ibn Fadlan’s account read more like a novel. But in many of Crichton’s scenes that use ibn Fadlan words, there are no major edits.

In saying all of that, this piece is not about this favored story but more about the repetitive “I saw…” statements in the translation and novel, specifically “I saw with my own eyes” and “I saw nothing with my own eyes.” And reflecting thru drawing how that seeing and witnessing is recorded and biases cast. In much of this years work, I think about how the past connects us with the present to remember how we tell our stories for the future.